Peering in the Window

At the age of eight I was taken by my parents to live in Europe. I felt not only uprooted from friends and life in Los Angeles, but for the first time in my life I felt different, strange, foreign. Plopped down in a small town in the Austrian Alps, I found myself sitting at a school desk listening to lessons in a language I did not understand as I began cataloguing the differences of appearance: fountain pens, handwriting of extraordinary control, briefcases, aprons, knitting lessons. Beyond the surface, the underlying discipline was palpable. The formal differences: bowing to teachers, walking in pairs in circles as recess, no boys in the classroom, sitting in the back of the class when the priest came to teach catechism, the penetrating stares of girls who had never seen a Jew before.

Within a couple of months German was fluent, but the language of the friendships eluded me. Perhaps the fact that the move was not permanent, that four years later California sun, swimming pools, and giggling slumber parties would replace a cold, snowy, and lonesome void, perhaps this knowledge prevented integration into the social life of schoolmates. In any event, four years of being foreign, outside the sphere of school, church or community, provided the opportunity to focus on the communication of non-verbal, highly critical visual language. This visual language was fed by travel at every opportunity. If mountains surrounding this provincial town were claustrophobic, each venture beyond brought a new friend – van Gogh in Amsterdam, Michelangelo in Florence, Toulouse-Lautrec in Paris – collections of postcards to memorize like family photo albums. Watercolors as bright as California took root in the depth of cold winters of coal and ash.

Naturally there is always the next lesson. You can’t go home. At twelve years of age, there was nothing unencumbered about returning to Los Angeles; not when the field trips of an early education included Anne Frank’s house, Dachau, and the battlefields of Verdun. In a Los Angeles of shiny, spit-polished, mirrored surfaces to inspire art of the most reductive obsessions, paintings of people spewed forth from my canvas. Paint was charged with emotion, symbolic in color, steeped in traditions absorbed without effort like the catechism acquired through osmosis in the back of the classroom. As a student in the art department at UCLA, the direction given was to go back to Europe. Graduate school followed in London at the Royal College of Art, where of course it was possible, down to the very nuance of vowels and volume, gesture, and body language, to spend years deep within a closed group while remaining very much apart and separate, and still speaking a foreign language.

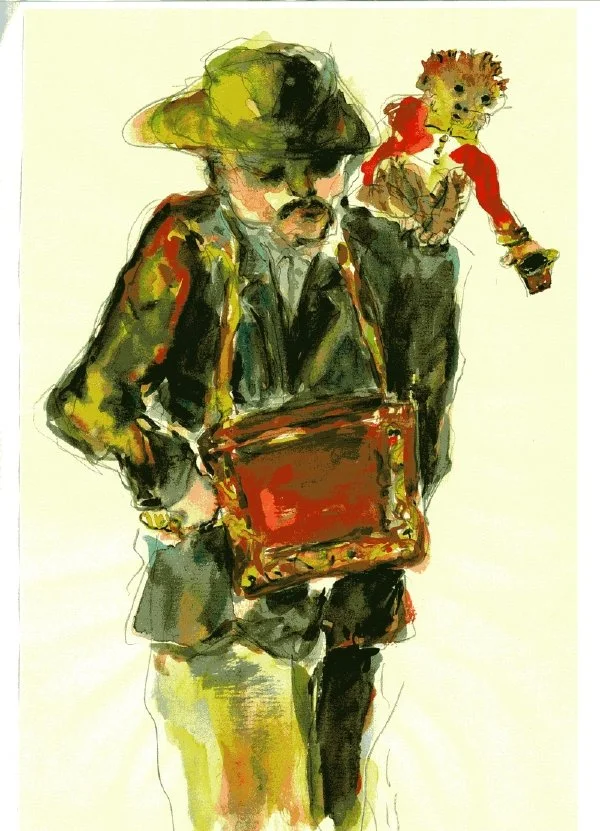

So decades passed in the studio: paintings of people eating, drinking, smoking, talking, not talking, not communicating, isolated, resigned to circumstance, deceit, divorce, suicide, loss, and mourning. These are the themes of paintings examining life from a distant perspective: the artist functioning beyond words, communicating in a visual language forged by the distance of being different, outside, peering in.

- Jan Wurm