Blog

When Red, Yellow, and Blue Sing

As the Twentieth Century dawned, painters could rest upon previous decades of color theory, research,

You’d Be Prettier If You Smiled – Identity, Gender, and Dissonance

You’d Be Prettier If You Smiled – Identity, Gender, and Dissonance

Storied Paper

The beautiful soft black line of the charcoaled half-burned twig, the luscious red stain of the smashed berries…

Outfitting Dreams and Dressing Our Wounds

We knew before we could explain it, and we knew it needed no explanation – it was right there for everyone to see...

Extension of the Artist’s Hand

This is a time for thinking about gifts and giving. I have just spent weeks calling friends…

What the Postman Brought

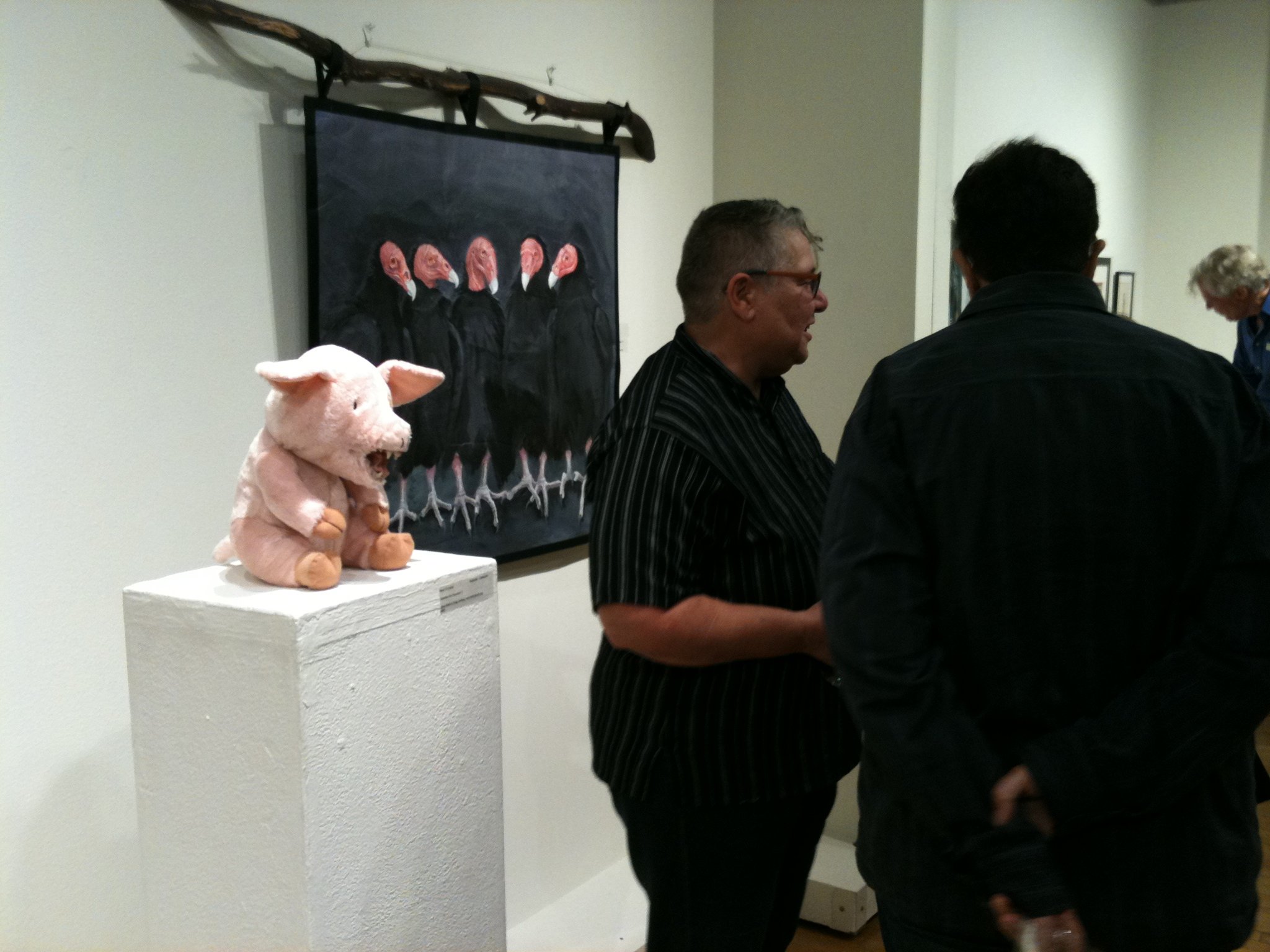

A call went out for Beasties, and the response slipped and slithered in: Creatures from the Black Lagoon, Slithery Serpents from under Black Rocks…

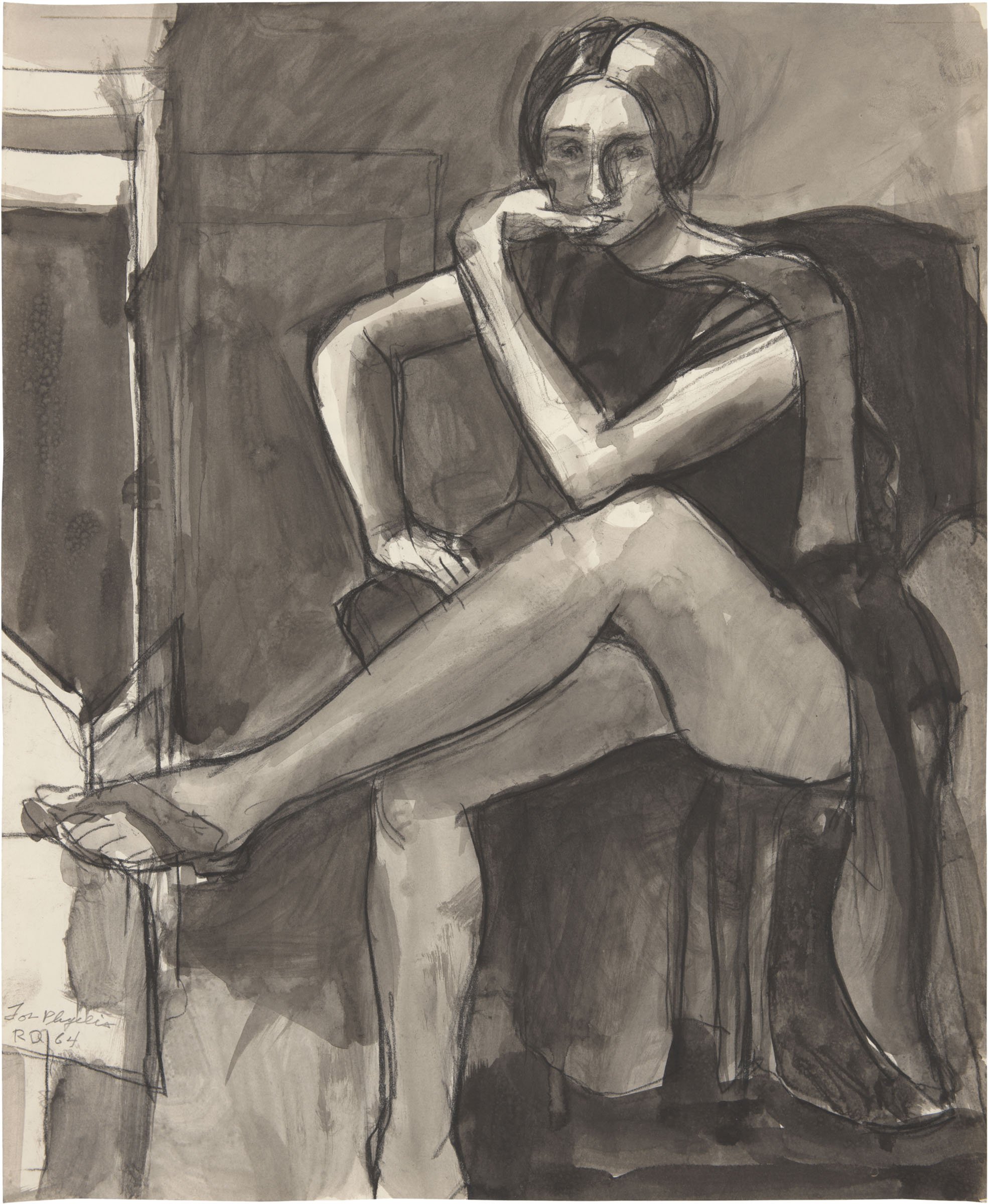

Reflections Following Closely Considered : Diebenkorn in Berkeley

As the exhibition, Closely Considered: Diebenkorn in Berkeley draws to a close, there seems to be a quiet moment – a pause between becoming/being and the finite has been…

The View From the Other Side

It is always an awakening to take on someone’s job. We come to appreciate the labor which goes unrecorded…

Living and Sustaining a Creative Life

New York Artist Sharon Louden has energized the Annual Conference for the College Art Association over the past few years by presenting some of the most valuable programming for studio artists…

Picturing a Post

The great hurdle has been picturing the act of writing a regular missive; the burning question has been whether this could maintain a level of interest for reading…

Travel of a Different Color

If you are heading out for parts unknown, a mini-trip through time will launch you at the San Francisco airport. …